ECPR General Conference, Prague: September 4-8, 2023

New Developments in Electoral Integrity Research

Section Chairs

Holly Ann Garnett (Royal Military College / Queen's University, Canada); Toby James (University of East Anglia, UK); Leontine Loeber (University of East Anglia, UK)

Abstract

Elections are an indispensable part of the democratic process (Dahl 1971). They give citizens an opportunity to elect their representatives, hold governments to account and shape policy making.

Yet it is well known there is enormous variation in the quality and inclusiveness of elections around the world (Norris 2014, 2016; Birch 2011; Norris 2013). An electoral cycle approach shows that problems can vary from cases of electoral violence and voter intimidation, vote rigging, gerrymandered electoral districts, incomplete electoral registers, through to under-resourced electoral officials and poorly designed adjudication processes, and more.

Challenges facing electoral integrity are commonly thought to be intensifying as illustrated by post-electoral violence in Brazil and the USA, the spread of disinformation online, under-funded electoral authorities, pandemic elections (James, Clark, and Asplund 2023, forthcoming; Garnett and Pal 2022).

This Section will therefore bring together the research agenda which is emerging to address conceptual, empirical and policy challenges to electoral integrity. Papers are welcome to address (but not limited to) the following themes:

• The nature of electoral integrity defects and emerging challenges to elections

• The effects of electoral integrity and malpractice, such as on voter confidence, democratic participation, political parties and policymaking

• ‘What works’ to improve electoral integrity, such as the management of campaign finance, election monitoring, disinformation strategies or voter registration mechanisms. We welcome Papers irrespective of their approach. Paper may include, for example, case studies, cross-national studies, analyses of surveys, or legal analysis.

This Section was hosted by the Electoral Integrity Project: an independent academic study founded in 2012, to facilitate innovative and policy-relevant research comparing elections worldwide.

The Section will meet to also make an application to develop an ECPR Standing Group at the conference.

PANELS

PRA069 – Campaigns and election finance

Electoral integrity does not only mean a clean process of casting votes, but also includes other areas of the electoral cycle. An important one is the way campaigns are run and financed. The papers in this panel look at the influence of money on electoral integrity, but also on the way campaign organisation can impact electoral integrity.

Chair: Toby James (UEA)

Co-Chair: Holly Ann Garnett (UEA)

Panel Discussant: Tom Barton (UoL, Royal Holloway College)

-

Authors: Kate Dommett (University of Sheffield) and Sam Power (University of Sussex)

Democratic elections should both be free and fair, and also be seen to be free and fair to engender public trust. One of the primary ways in which these qualities are ensured is through transparency mechanisms. And yet, these transparency mechanisms are neither a panacea, nor implemented in the same way across the world. However, advances in technology pose an opportunity. In particular automation provides an invaluable new weapon in the fight to uphold the integrity of the electoral process. Currently, regulators struggle to keep up with technological developments that evolve faster than national (or supra-national) legislation can keep pace with. In this context, transparency is all the more important, as is the ability to analyse donation and spending returns in near-real time. In this paper we utilise elite interviews with EMBs across the world that are experimenting with automation to address three questions: Where is the potential to use automation? What capacity is needed to realize these goals? What are examples of how automation is utilized? In doing so we explore a fascinating new frontier of upholding electoral integrity of interest to academics, activists and practitioners alike.

-

Author: Anna Frydrych-Depka (Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland)

In my paper I will present a case study of the first Polish election-related monitoring of the abuse of state resources prepared for the upcoming parliamentary elections by a coalition of civil society organisations led by the observers’ NGO (Political Accountability Foundation). It will highlight the decision making process (if, what, with whom and how to observe), as well as possible challenges for the implementation of IFES and NDI’ guidelines.

One of the current challenges for electoral integrity is the abuse of state resources prior and during the electoral campaign. Unfortunately, use of state resources during electoral periods is not sufficiently regulated and enforcement of violations is weak mainly due to the lack of political will and limited capacity of oversight institutions. Limited citizens’ interest in changing the landscape is also an issue in this matter. Individuals and parties in power may easily capitalize on these gaps to marshal public goods – personnel, funds and physical assets, and official government communications – in service of political campaigns. It undermines competitiveness by giving an unfair electoral advantage to incumbents and disturbs one of basic electoral principles -equality of opportunity for all candidates.

As it is stated in the Venice Commission and OSCE/ODIHR's Joint Guidelines for Preventing and Responding to Misuse of Administrative Resources during Electoral Processes, domestic election observers have a crucial role in reporting on potential misuse of administrative resources and proposing recommendations to strengthen legislation and practice (point 3.5). Moreover civil society can raise awareness among citizens and political stakeholders of the importance of a fair use of administrative resources during electoral processes (point 4.3). Reporting from the one hand and educating from the other may seem like standard tasks of domestic observer organizations. The topic of how to prepare and conduct successful monitoring is covered by IFES and NDI in their comprehensive and user-friendly publications (Abuse of State Resources Research and Assessment Framework: Guidelines for the Democracy and Governance Community of Practice, How Citizen Organizations Can Monitor Abuse of States Resources in Elections: an NDI Guidance Document). But even with such good theoretical background, there are plenty of practical challenges for an observation mission to handle. In the Polish case the main questions are: how to work in a difficult environment characterised by the lack of political will for reforms and a plethora of obstacles such as limited access to public information and politicised audit institutions? How to communicate about the results of such an observation in a way that engages the public and raises awareness about the issue, especially among ruling party supporters? And last but not least will this monitoring exercise even work and lead to the strengthening of election integrity in Poland?

-

Author: Viktoriia Poltoratskaya (Central European University)

This paper attempts to look into the influence of proximity to large companies on electoral results in local electoral committees during federal parliamentary and presidential elections in Russia. It is proven that companies of certain types are used as a platform for mobilisation of voters through various incentives. According to Frye et al. (2014, 2019) – firms and their employers are extremely important for providing the ruling party with necessary support in Russia. As was discovered (Frye et al. 2014), if the company is a part of the state-supported or state-owned industry, or the one with immobile assets or monopoly on providing population in locality with working places – it is more likely to be a broker in the clientelistic exchange. This work tries going a little further and checks if the presence of large companies in general can be considered a factor influencing the party performance or the electoral results of the president. Some media reported a well-established scheme of brokers being assigned to the large local companies and working with its employees to make sure they will attend the elections and vote accordingly (Kozlov 2018, Kuhmar’ 2020).

The data for analysis was collected from the Central Electoral Committee and a company register. This data was then matched by the geographically nearest distance between local electoral committees and large companies calculated in metres using the vantage-point tree approach, resulting in a dataset containing 92,875 observations with 14,300 unique companies. The distribution of observations shows that the density of electoral committees is higher and the coverage is better, while large firms are more likely to be concentrated around economically better performing territories.

A logistic regression and linear regression was conducted to study the relationship between the distance to the nearest large company and the electoral results registered at local electoral committees. The results from the logistic regression showed that for federal parliamentary elections, the probability of the local electoral committee to show the lowest share steadily increases as the distance between the voting place and the large company increases. For presidential elections of 2018, the probability of getting into the first group with the lowest share of votes gets up to three times higher with the increase in distance. The linear regression models also showed negative coefficients for distance and number of registered voters when predicting turnout and share of votes in both federal parliamentary and presidential elections.

-

Author: Holly Ann Garnett (University of East Anglia)

Does the amount of money a candidate spends on their campaign have an impact on their success in their local race? There are many studies, from both the Canadian and international context, that consider the relationship between money and electoral success at the district level. They all begin with a similar hypothesis: the more money a candidate spends, the more people they can reach with advertising and canvassing, and the more publicity, the more votes they are likely to get. But all these studies also outline a key challenge: the ability to raise money and the ability to win elections are likely caused by the same factors. Two of these major factors are candidate quality and the probability the candidate is going to win. The same factors that make a candidate appeal to voters – be that their experience, qualifications, or charisma – will make the candidate appeal to donors (since donors are voters and vice versa). Additionally, individuals donate to candidates who have some chance of success. In other words, why invest money in a campaign that is unlikely to win? This problem of endogeneity is the central challenge studied by scholars seeking to uncover the relationship between money and electoral success, beginning as early as the 1980s to the present day. This paper considers the relationship between spending and electoral success in electoral districts during the 2019 Canadian federal election. After exploring the main solutions proposed to the problem of endogeneity between spending and electoral outcomes, it presents three possible methods to model this relationship, using data from candidate expense data, candidate characteristics, district-level census data, and electoral outcomes. It finds that for all modelling strategies, spending by a local candidate is significantly related to their vote share, demonstrating that money really does matter for electoral outcomes in Canada.

PRA105 – Concepts of electoral integrity

When discussing electoral integrity, different concepts are used, but not always in a clear defined way. The papers in this panel aim to clarify or define these concepts, such as election fraud, electoral competitiveness and election quality

Chair: Toby James (UEA)

Panel Discussant: Anna Unger (Eötvös Loránd University)

-

Author: Juliette Ruaud (Université de Paris I – Panthéon-Sorbonne)

The issue of electoral integrity is a persistent concern, particularly in first-time electoral contexts. Based on a micro-sociological case study, this paper aims to provide an overview of an ongoing revisit of a study conducted between 1956 and 1959 at the behest of the Belgian colonial government. This fieldwork was carried out during the first instance of universal male suffrage in Rwanda and Burundi, then Ruanda-Urundi, and was the first of its kind in Africa. The research team comprised two Belgian ethnographers, Jean-Jacques Maquet and Marcel d’Hertefelt, along with the help of civil servants of European and African descent. They organized several mock elections, with the aim of testing and refining electoral technologies before their implementation. They also observed the first elections in real conditions, collected hundreds of written testimonies, and analyzed and mapped the results. Meanwhile, the colonial demographic and statistical services conducted an opinion survey among 3,500 voters. Both studies provide insight into how electoral malpractice was conceptualized and feared in this context. In particular, they provide insight into how the issue of electoral integrity has been linked to the issue of voters' "learning" to vote correctly and dealing with an unknown technology. In this regard, the paper will analyze the (often forgotten) educational projects and the technological innovations of the time, then supposedly intended to mitigate the risk of electoral fraud. By re-examining these anthropological writings against the grain and comparing them with archival records and the materials collected at the time (notebooks, interviews, photographs, films, etc.), we can enhance our understanding of a relatively unknown aspect of electoral observation's history. This will facilitate a discussion on the evolution of the actors and methodologies involved in the formation of expert knowledge in the field of vote governance and electoral integrity, as well as its colonial origins. Combined with a study of the reception of this work in the 1950s, it will also offer a better understanding of the interconnections between the social sciences and various forms of expertise in electoral monitoring and integrity implemented on the African continent since decolonization. Most importantly, this research will provide a new historical perspective on the ways in which political scientists understand electoral integrity, especially in former colonized countries, that can inform current research. In brief, this paper aims to demonstrate how recent research in historical sociology and colonial history can contribute to electoral integrity research.

-

Authors: Holly Ann Garnett (University of East Anglia) and Toby James (University of East Anglia)

Elections are indispensable for the democratic process. The quality of elections has been shown to vary enormously worldwide and have important consequences for democratic participation, peace and security. Recent scholarship on electoral integrity has led to enormous advances in understanding the policy mechanisms for improving the quality of elections (Norris, 2014, 2015, 2017). Despite this, there remains an unresolved debate about what, in conceptual terms, electoral integrity is and how it can be adapted in response new threats from autocrats and subversive actors. This paper introduces a new conceptual framework for understanding electoral integrity by drawing from democratic theory. It then offers a way of measuring electoral integrity through a revised version of the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity Index. The approach is critical analyses and important lessons drawn for prescribing best practices to defend and rich democracy, as well as major scholarly implications for the study of democracy, democratisation, comparative politics and beyond.

-

Author: Leontine Loeber (University of East Anglia)

There has been a considerable increase in the academic attention that is paid to election fraud in established democracies, in recent years. Electoral fraud is problematic because having clean elections is necessary for the trust of citizens in their government. However, although the term “election fraud” is often used in law, there is no agreed legal definition of what actions are and are not election fraud; legislation therefore differs from country to country. To date, there is no explanation of why these differences in legislation occur.

This paper seeks to make both an empirical-descriptive and a theoretical contribution to how election fraud legislation is shaped. The empirical-descriptive contribution is made by providing a summary of two in-depth case studies that were part of a larger thesis. These case studies show the historical development of election fraud legislation in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom in the period of 1830-2020, based on parliamentary records. While some accounts have been provided on this topic for the United Kingdom, very little has been written about the Netherlands. Comparative research on election fraud rules for established democracies is nearly absent.

The paper aims to make a theoretical contribution to explaining why electoral laws take the form that they do, by focusing attention on the previously unnoticed role of legislatures and courts in this part of election administration. The paper also provides a new analytical tool for comparing electoral fraud legislation in different countries. An original matrix is developed by the author to enable the comparison of the main properties and characteristics of legislation that can be used for comparative research.

This paper provides new insights with regard to the question of what is legally considered election fraud and why this differs between countries. These insights can be useful for both country-specific policies and the practical field of electoral assistance and election observation.

-

Author: Anna Unger (Eötvös Loránd University)

Democratization, consolidation, de-consolidation, de-democratization and autocratization studies are among the most fashionable research topics in political science. More and more research projects have been launched for measuring democracy, creating dozens of different databases, indices, with many different methodological backgrounds, from quantification of the key aspects of the political system and civic liberties (Freedom House, V-Dem) to the perceptions of experts about electoral integrity (EIP). Furthermore, single cases as country-studies become more and more relevant, again, and their results are available in many papers and books about the non-democratic regimes (competitive authoritarian hybrid regimes, electoral autocracies, competitive autocracies, constitutional autocracies, populist regimes, hybrid regimes, defected democracies, illiberal democracies – as you like).

The most common, most popular definition for contemporary non-democratic regimes is probably ’competitive authoritarian hybrid regime’. Scholars find that in these kind of hybrid regimes real political competition is present in that sense the opposition parties run and may have a tiny chance to win, though the electoral contest is quite unfair and unequal, as the playing field of politics (including elections) is uneven. In this approach, competitiveness is a set of rules, features and behaviors practiced by the government and state authorities, and is quite close to the meaning and content of ’fair elections’. One could easily argue that fair elections are competitive ones, or, that the features of competitiveness result fair elections.

However, this meaning of competitiveness denies the Sartorian one, where competition is a key, distinctive feature of democracy. Consequently, if something is not democratic, it cannot be competitive, and vice versa, if something is competitive, it cannot be non-democratic (authoritarian). Following his classic explanation, a distinctive feature cannot be a question of degree (how much?), but only a question of kind (either/or).

And to make these even more confusing, in Electoral studies, competitiveness is usually referred as simply the level of contestation among the candidates (and also serves as an indicator of incumbency advantage).

Whichever approach we take, it is clear that competitiveness has become a key concept of elections. This paper argues that we have to (re)conceptualize competitiveness as a core concept of electoral integrity, for avoiding the classic trap of conceptual over-stretching. After the analysis of the three abovementioned approaches of competitiveness, the paper explains the problem through the case study of Hungary, where the constant alteration of electoral rules and the changing environment of elections by the government (including media, advertisement market, electoral management bodies, law enforcement, and so on) has not only changed the social-political landscape of the country, but led it into a state of electoral autocracy. And, at this point, the question of competitiveness becomes essential: for the opposition, for international actors, for the society, because the nature of elections (whether it is still competitive or not) fundamentally affects the behavior and political strategy of all these actors, and therefore the chances of democratization by elections.

PRA300 – Manipulation of elections

Election manipulation is happening in many countries in the world. The papers in this panel look at that issue from different angles.

Chair: Sam Power (University of Sussex)

Co-Chair: Toby James (University of East Anglia)

Panel Discussant: Carolien Van Ham (European University Institute)

-

Author: Maria Linden (Tampere University)

Since Donald Trump attempted to abuse his powers as President to manipulate the 2020 presidential elections, many experts have voiced concern over the future of American democracy. More specifically, many have warned that the Republican party is preparing to resort to undemocratic means to secure a victory in the 2024 presidential elections. The United States has several well-documented issues with electoral integrity; in their 2019-2021 report, The Electoral Integrity Project ranked the country lower on their electoral integrity index than any other liberal democracy.

Drawing on information gathered from newspaper articles and reports by nongovernmental organizations, analyzed using a novel framework, this paper focuses on electoral manipulation by the Republican party in 2021 and 2022. It answers the following questions: 1) Did the Republican Party resort to the same electoral manipulation tactics in 2021-2022 than Trump did in 2020?, 2) What did the Republican Playbook of Electoral Manipulation look like in this time period? and 3) Did the Republican Party undertake acts of electoral manipulation in 2021-2022 that could pose a risk to the integrity of the 2024 elections? By further developing the author’s framework for analyzing electoral manipulation and applying it in a timely case study, the research provides new information about the nature of electoral integrity defects and emerging challenges to elections in different stages of the electoral cycle.

This paper finds that the Republican party has been engaging in acts of electoral manipulation akin to those of Trump in 2020. The present-day Republican playbook of electoral manipulation consists of seven tactics: 1. Breaking democratic norms, 2. Disinformation, 3. Gerrymandering, 4. Voter suppression, 5. Intraparty pressure, 6. Intimidation and violence, and 7. Attacking state and government institutions. With the exclusion of gerrymandering, which does not apply to Presidential elections, these same tactics were also part of Trump’s 2020 playbook. It is also notable that the present-day Republican playbook contains all the tactics utilized by Trump in connection with the 2020 elections except for collusion with one ore more foreign states. While some of the tactics in the playbook have been a common feature of American politics for decades or even centuries and some of them are used by Democrats and Republicans alike, the power of the playbook lies in how the combination of tactics creates a whole that is larger than the sum of its parts.

The paper finds that several of the acts of electoral manipulation undertaken by the Republican party in 2021-2022, such as spreading disinformation that undermines confidence in American elections, inserting election deniers into election administration and passing laws that make attacking institutions easier, pose a risk to the integrity of the 2024 elections.

-

Authors: Masaaki Higashijima (University of Tokyo) and Matthew Wilson (University of South Carolina)

By unpacking how autocrats design elections, recent research on autocracies start investigating when dictators rig elections by using what electioneering strategies as well as what implications those electoral strategies may have on regime stability. However, we know little about how election management bodies (EMBs) – one of the most important institutions affecting the electoral battlefield – influence the dictator’s tool box to manipulate election results and impact authoritarian durability.

EMBs have two important aspects which affect dictators’ electioneering strategies; capacity and autonomy. EMB capacity refers to the ability of administering national elections by mobilizing staff, financial and organizational resources to reduce glitches distorting electoral integrity; EMB autonomy means EMB’s political independence from the government to apply election laws and administrative rules impartially in national elections. When EMB capacity is high, autocrats can effectively orchestrate covert forms of electoral manipulation and thus hold elections with stable pro-regime results. Such strong organizational capabilities for election management make autocrats less incentivized to employ overt forms of electoral manipulation such as vote buying and blatant electoral fraud. By contrast, when EMB autonomy is high, dictators cannot preemptively bias election results in favor of themselves. Under such conditions, autocrats are more tempted to resort to the overt forms of fraud to secure overwhelming election victories.

In addition to techniques of electoral manipulation, EMBs also have significant implications on regime survival. Since high levels of EMB capacity enable dictators to manipulate election results implicitly and overwhelming election victories lead to credibly demonstrate their power at elections, they are more likely to make the regimes resilient. By contrast, EMB autonomy ties autocrats’ hands, which make it difficult for them to extensively manipulate elections. Furthermore, the overt means of electoral manipulation often induce backlashes from the opposition and masses, paving the way for autocratic breakdown. Put differently, our theory expects that the EMB capacity is positively associated with autocratic survival whereas the EMB autonomy is negatively correlated with autocratic survival.

We test these hypotheses on a cross-national data set. We first find EMB capacity is positively associated with ex ante forms of electoral manipulation such as the reduction of electoral pluralism and negatively associated with over forms of manipulation techniques such as vote-buying and ballot-stuffing. In contrast, EMB autonomy is positively associated with electoral pluralism as well as these overt electoral fraud. We also find that EMB capacity tends to prevent autocratic breakdown, while EMB autonomy tends to negatively impact autocratic durability. Our theory and empirical analysis suggest that EMBs are a pertinent institution which significantly impacts the electoral field and regime resilience also under the authoritarian context.

-

Author: Hager Ali (German Institute for Global And Area Studies)

Though regime collapse and military coups played an important role in the ongoing surge of authoritarianism, autocratization is also creeping, incremental and – unlike regime breakdowns – more difficult to quantify. This will paper will investigate incremental regime transformations through constitutional and electoral reforms in hybrid and authoritarian regimes.

There is consensus in existing research that constitutional and electoral reforms are an important tool in opening or restricting democratic systems by changing the parameters of electoral competition. However, the study of electoral or constitutional reforms and their impacts is also narrowly focused on major reforms in Western European polities even though they take place in any regime, regardless of its type. Elections take place across non-democratic regimes as well and autocratic incumbents strive to ensure apparent electoral success for various reasons ranging from legitimacy to criminalizing the opposition. The analysis is driven by two main questions: What kinds of constitutional and electoral reforms take place in hybrid and authoritarian regimes? And how do they differ from reforms initiated by incumbents in democracies? By revisiting the classic literature on electoral and constitutional reforms in democracies, the goal of this paper is to build a conceptual framework to systematically classify constitutional and electoral reforms and compare them across regime types.

-

Author: Jaroslav Bílek (Charles University)

Are incumbents in electoral authoritarian regimes choosing between different forms of electoral manipulation based on their direct and indirect costs? Despite the vast research agenda on this topic, no global cross-national analyses with newer cases are available. While using a dataset that includes 340 elections in 68 electoral authoritarian regimes from 1980 to 2020, this study aims to fill this gap and explore how incumbents decide between different tactics of electoral manipulation. Results reveal that direct and indirect costs rarely affect choosing between different types of electoral manipulation. Instead, the study finds that incumbents are likely to deploy most or all types of electoral manipulation at once if they have the opportunity. Moreover, contrary to the theoretical expectations, the more uncertain the electoral outcome is, the less electoral manipulation is employed. The study contributes to the understanding of electoral authoritarian regimes by debunking the myth prevalent in the literature.

PRA333 – New developments and electoral integrity

Several new developments have an impact on the integrity of elections and the way elections are run. One of such developments is the issue of misinformation, that is used more and more to cast doubts about elections. Also, there have been emergencies that have an effect on elections, such as natural disasters and recently the Covid-19 pandemic.

Chair: Leontine Loeber (University of East Anglia)

Panel Discussant: Masaaki Higashijima (University of Tokyo)

-

Authors: Holly Ann Garnett (University of East Anglia) and Toby James (University of East Anglia)

Emergency situations caused by natural and technological hazards have often been thought to pose a major threat to democratic practices. The COVID-19 pandemic was a critical case which was thought to pose as a major threat to election quality and democracy worldwide. Although there have been many country-specific studies of the effects of the pandemic, cross-national analysis has been limited due to the unavailability of data. This article introduces the concept of electoral integrity resilience as the configuration of actors, resources and properties which enable societies to adapt to an external shock which could damage electoral integrity. It then uses a new original dataset to identify the effects that the pandemic had on electoral integrity in national elections during 2020-22, which covers the whole electoral cycle. It finds that the electoral campaign was the most affected aspect of the elections. It then identifies the properties of polities which had the greatest resilience to the pandemic. The article has important lessons for the study and praxis of how future national and global risks can be prepared for and the construction of strong institutions.

-

Authors: Zuzana Haase Formánková (Institute H21), Ivan Jarabinský (Institute H21), Jan Oreský (Institute H21), Miroslav Líbal (Institute H21)

Different electoral rules come with various complexity of voting. Plurality voting, as the easiest-to-use voting method, is still among the most utilized voting systems in the world despite electoral experts repeatedly rating it among the worst voting methods available for many reasons: for example, a large number of wasted votes and its ability to choose a Condorcet’s loser (Laslier, 2011). However, it benefits from its simplicity which contributes to a proper, fair, and legible electoral process: with a single vote, the system is easy to use for voters and easy to administer for electoral authorities. The issue of a higher electoral systems’ complexity stands as an important argument when electoral reform is considered. Potentially increased voter error rates raise a challenge for a democratic process, especially if it impacts various sociodemographic groups of voters unevenly.

To test the voters’ ability to cast a valid vote for a candidate or candidates they prefer, we run an experiment with a within-subject design, simulating a voting process with different electoral methods. Preceding the Czech presidential election in 2023, we asked two representative samples of Czech citizens to cast their votes both using the paper ballot (n=1357) and in an online environment (n=912). Every participant voted in six electoral methods, which were chosen to represent the broadest possible range of voting rules that are repeatedly discussed as possible replacements for plurality voting. Thus, we tested one voting method from the following types: single vote, approval, multiple votes, ranking, and grading. Moreover, we employed a method with a limited number of plus and conditional minus votes, which we expected to be the most difficult one for voters with complex instructions. The collected survey data allow us to draw conclusions on which electoral systems are prone to invalid voting and expand our knowledge about voters’ ability to adopt new electoral methods. Our data also show the character of voter errors, how voters’ attention and ability not to make mistakes differ in offline and online environments, and how it is based on individual factors.

Preliminary results show that the amount of mistakes voters make is independent of the number of votes they are allowed to use, as we did not report an increase in invalid votes in the three-vote or approval method compared to plurality voting. Voters cast a mismarked vote significantly more often in a system inquiring voters to evaluate the fulfillment of a condition. However, we found the highest error rates in the alternative vote, where 8.5 % of the voters did not cast a valid vote. This finding is especially important because alternative voting is most often considered a valid substitute for plurality voting. Yet, it is also the one with the highest complexity, which jeopardizes the ability of voters to participate in the democratic process.

References:

Laslier, J.-F. (2011). And the loser is… plurality voting. In Electoral systems: Paradoxes, assumptions, and procedures (pp. 327–351). Springer.

-

Author: Basak Bozkurt (University of Oxford)

A broad range of actors, including politicians, foreign states, bots, and trolls, disseminate election disinformation on social media, which can decrease voter turnout, diminish trust in election results and ultimately undermine public confidence in the overall democratic process. Despite increasing concerns, the impact of disinformation on electoral integrity has not been thoroughly explored. Apart from a few studies focusing on the effects of cyber threats (Garnett & James, 2020; Garnett & Pal, 2022; Judge & Korhani, 2020), there has been limited focus on election disinformation in the electoral integrity literature.

The objective of this paper is to analyse and bridge key gaps in the research on election disinformation and electoral integrity. To achieve this, it will synthesise insights from the disinformation studies and electoral integrity literature, drawing on empirical evidence from the former and theoretical frameworks from the latter. This paper will provide recommendations on addressing these gaps to advance our understanding of the challenges facing democracy today.

The first gap is that the impact of election disinformation has not been fully incorporated into statistical analyses in the electoral integrity literature. Much research has focused on the impact on electoral integrity of electoral management bodies, the judiciary, the media, civil society, and international and domestic monitoring organisations (Asunka et al., 2019; Birch & Van Ham, 2017; Hyde & Marinov, 2014). The disinformation ecosystem has not been considered a factor affecting electoral integrity, despite the relevant data being available. A widely used dataset, the V-Dem, for example, includes indices on coordinated information operations, including the dissemination of false information by governments, foreign governments, and parties. Such indices can be a good starting point to analyse the impact of disinformation on electoral integrity.

Another gap is that the circulation of disinformation by politicians has not been included in the “menu of manipulation” (Schedler, 2002). Empirical findings suggest that domestic politicians are now believed to be more active than foreign actors in spreading disinformation (Benkler et al., 2020; Warren, 2020). Arguably, therefore, the spread of disinformation should be included in the menu of manipulation employed by politicians. The conceptual framework from electoral manipulation theory can guide researchers to explain the rationale behind politicians’ strategies in disseminating false claims.

In addition, despite the wealth of research on election monitoring, social media monitoring (SMM) remains a significant gap in the literature. Until recently, monitoring activities were conducted by domestic and international organisations using traditional methods, such as monitoring polling stations. However, as these methods are inadequate in detecting and countering disinformation, monitoring organisations have begun SMM. Therefore, there is a need to investigate the impact of SMM on electoral integrity. Moreover, SMM companies (e.g. BrandWatch, which the EU has employed to track Russian influence (Schmuziger Goldzweig et al., 2019, p. 15)) remain among the key players yet to have been fully recognised in the literature. Studies should examine the impact of these actors on electoral integrity.

PRA420 – Public perceptions of elections

Trust in elections is important. Without such trust, the legitimacy of the outcome of elections is in danger. The papers in this panel look at public perceptions of electoral integrity, with two papers focussing on the trust that Germans have in their elections and one paper that public perceptions in 25 countries.

Chair: Anna Frydrych-Depka (Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland)

Panel Discussant: Holly Ann Garnett (University of East Anglia)

-

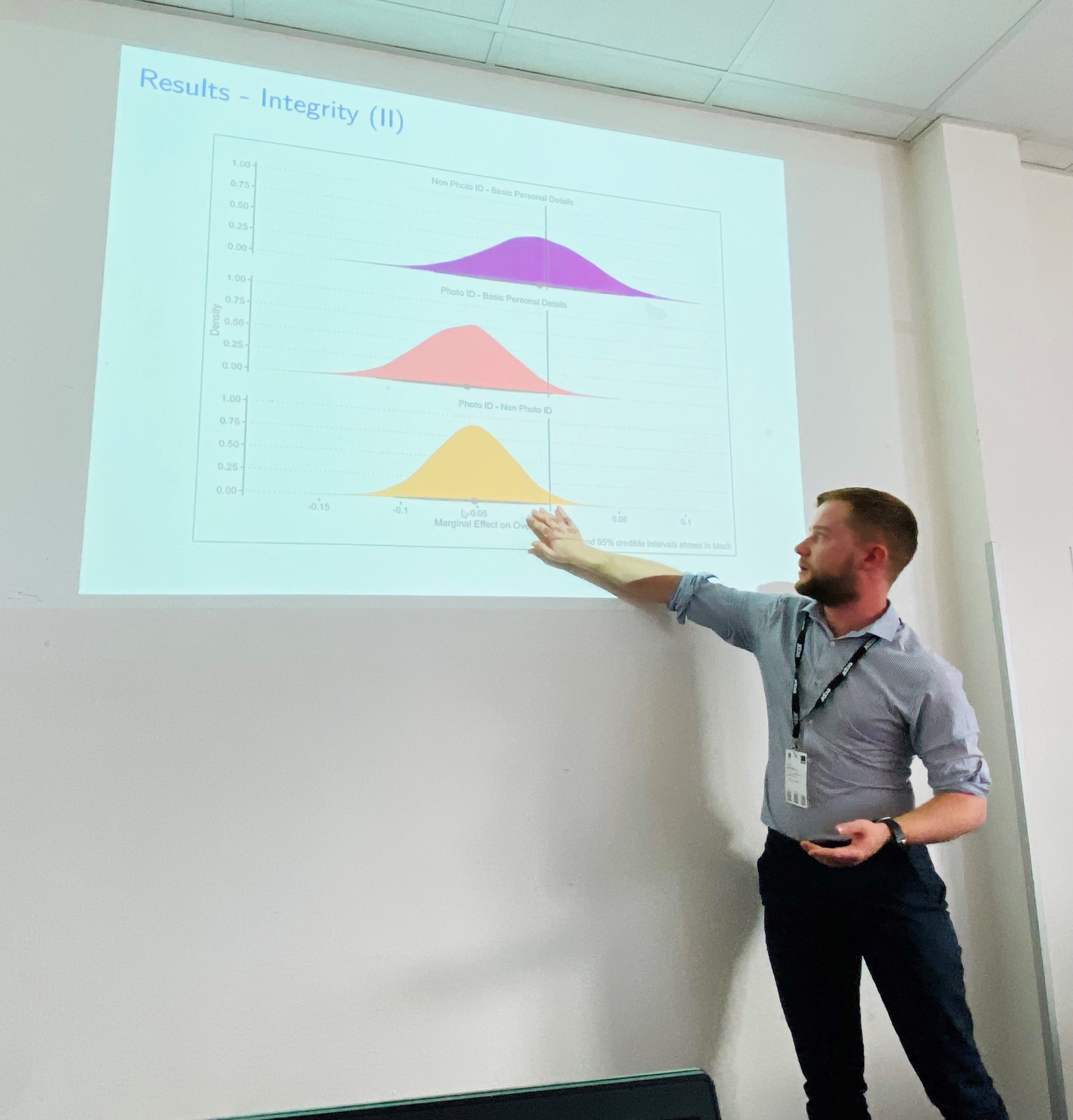

Author: Tom Barton (University of London, Royal Holloway College)

A key component of democratic legitimacy is electoral integrity. Elections are said to have integrity when the will of the people is genuinely reflected in the outcome of the election. But elections lacking integrity can show elements of fraud, malpractice and manipulation. However, the role voter Identification (ID) laws play in ensuring or limiting integrity is not well understood. We know from previous research that more restrictive voter ID laws are associated with lower election turnout. Therefore, it may be argued such laws may limit the extent to which the genuine will of the people is reflected. Yet a key argument for voter ID laws is that they prevent malpractice and fraud, in which case restrictive voter ID laws should enhance electoral integrity. This paper tests these competing claims using an original dataset of voter ID laws in 196 countries combined with the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity dataset and shows that more restrictive voter ID laws (based on photo ID) are associated with lower perceptions of electoral integrity at the national level. To test the direction of causality, analysis of a panel study of the United States shows when a more restrictive voter ID law is introduced perceptions of integrity improve. The implications of these findings are in a response to, lower levels of integrity more restrictive voter ID laws are introduced. This contradictory finding implies that restrictive voting laws may only act as a short-term solution to lower integrity and not deal with the root causes of low electoral integrity.

-

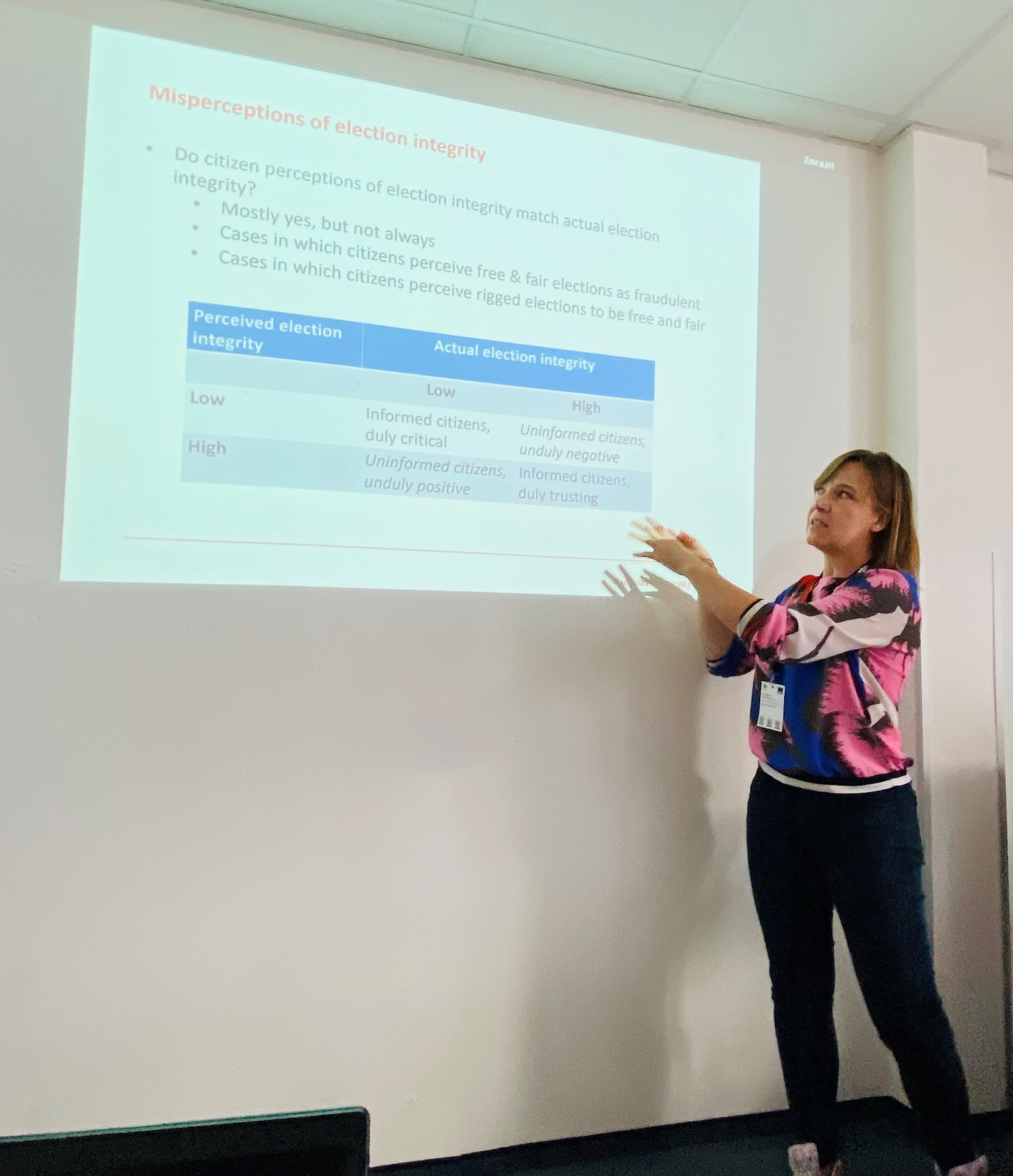

Authors: Kristof Jacobs (Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen), Sanne Kruikemeier (University of Amsterdam), Carolien van Ham (Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen), and Rens Vliegenthart (Wageningen University and Research Center)

Accurate citizen perceptions of election integrity are essential for democracy. If elections are rigged, ideally citizens would notice and mobilize and protest to hold their government to account and push for clean elections. Conversely, if elections are clean, ideally citizens would notice this as well, so elections can legitimize the elected government, foment political trust, satisfaction with democracy, and acceptance by citizens of decisions made by the elected government. Misperceptions of election integrity, on the other hand, can be problematic for democracy. They may lead to either unduly positive or unduly negative evaluations of election integrity by citizens. If elections are rigged and citizens perceive them to be clean, elections with low levels of election integrity may nevertheless help to legitimize and stabilize electoral authoritarian rule. Conversely, if elections are clean and citizens perceive them to be rigged, elections may end up triggering unwarranted civil conflict and destabilizing democracy (cf. the United States and Brazil).

In this paper, we study (mis-)perceptions of electoral integrity in 25 countries using novel survey data collected in February 2023 in a variety of countries across the world with different levels of electoral integrity and combine these with EIP’s Perceptions of Electoral Integrity expert data. We build on the burgeoning literature on citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity (a.o., Bowler et al. 2015, Kerr 2018, Lundmark et al. 2020, Coffé 2017, Norris et al. 2020, Enders et al., 2021; Flesken and Hartl, 2018, Karp et al., 2018, Mochtak et al. 2021) and propose an information-seeking and processing account of misperceptions, bringing in insights from political communication research on social identity theory, selective exposure mechanisms and echo chambers, as well as insights on the different roles of social media in different regime types (Theocharis et al. 2017).

We argue that misperceptions of election integrity are likely to be driven to an important extent by (1) the different sources of information available to citizens and (2) the degree to which they trust those sources. We include a wide array of sources, ranging from direct experiences with elections by participating in them, to information gained from social networks as friends and family, to information via politicians, to information via social and traditional media. The extent to which citizens trust these sources will likely determine the impact of information available on (mis)perceptions of election integrity. We expect in general that some of these sources, most notably social media, are most likely to spread misinformation about elections, and therefore are most likely to increase misperceptions of election integrity, whereas traditional media should decrease misperceptions of election integrity. However, we expect these differences to be (partly) context-specific. In contexts where media freedom is low and traditional media is likely under significant control of incumbent governments, social media more often serve as an alternative source of correct information, and we, therefore, expect this relationship to reverse: with citizens who trust traditional media being significantly more likely to misperceive election integrity than citizens who are more trusting of social media.

-

Authors: Arne Carstens (Freie Universität Berlin), Thorsten Faas (Freie Universität Berlin), and Aiko Wagner (Freie Universität Berlin)

Debates about perceptions of electoral integrity have finally reached Germany in recent years. With the "Alternative for Germany", a right-wing populist party has established itself in the German party system that repeatedly and systematically questions the integrity of electoral processes. Absentee voting is growing significantly in popularity - a factor that is time and again associated with issues of electoral integrity and, moreover, has experienced a popularity boost as a result of the Corona pandemic. Finally, recent elections in Germany have also produced very different outcomes (and government compositions) - the relevant literature has also repeatedly linked the outcome (i.e., winning or losing) of an election to perceptions of electoral integrity. The common feature of these various factors – populist attitudes and actors, absentee voting, winning/losing an election – is that there are no objective links between them and electoral integrity; rather, they are mere projections. In fact, the quality of elections worldwide has been evaluated by the Electoral Integrity Project ever since 2012. The project attested high electoral integrity to the two German federal elections examined so far (2013 and 2017), achieving scores of 81 (2017) and 80 (2013) on the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity Index. This puts Germany in 6th place among the 167 countries included in the study. Only the Scandinavian countries fared slightly better. But even that has changed recently in Germany: The elections that took place in Berlin in September 2021 were marked by massive glitches and problems: long waits outside polling stations, temporary closures of polling stations, and problems with ballots. As a result, the Berlin Constitutional Court ruled that the 2021 state elections were null and void and the entire election had to be repeated. This repeat state election took place in February 2023. Based on various surveys - representative polls on the 2017 and 2021 federal elections, but also studies on the Berlin repeat election - we want to use the proposed paper to analyze the extent to which perceptions of electoral integrity are shaped by the actual experience of electoral breakdowns and problems, by winning or losing elections, or else by projections of predispositions.

Bibliography

Birch, Sarah. 2011. Electoral Malpractice (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

Dahl, Robert. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (Yale University Press: New Haven).

Garnett, Holly Ann, and Michael Pal (ed.)^(eds.). 2022. Cyber-Threats to Canadian Democracy (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press).

James, Toby S., Alistair Clark, and E. Asplund (eds.). 2023, forthcoming. Elections during emergencies and crises: lessons for electoral integrity from the covid-19 pandemic (International IDEA: Stockholm).

Norris, Pippa. 2013. 'The new research agenda studying electoral integrity', Electoral Studies, 32: 563-75. ———. 2014. Why Electoral Integrity Matters (Cambridge University Press: New York). ———. 2016. Strengthening Electoral Integrity: What Works? (Cambridge University Press: New York).