By Pippa Norris, Holly Ann Garnett, and Max Grömping

This report was published as "Electoral Integrity in all 50 states, ranked by experts" in Vox on 23rd December 2016.

Ever since Bush v. Gore in 2000, the way that American elections are run has become increasingly partisan and contentious. The 2016 elections ratcheted up the record number of complaints by all parties. Like many issues in contemporary American politics, there is heated disagreement about the nature of the problem – let alone any potential solutions. It does not help that news headlines are fixated on a shiny bauble of a non-issue – alleged voter fraud - whereas far more fundamental flaws in American elections continue to go unaddressed, including problems of partisan gerrymandering, campaign media and political finance. As we head into a forthcoming report by the intelligence community and bipartisan Congressional investigations into hacking, what else should be on the agenda to strengthen electoral integrity?

Potential flaws in American elections

Fraud

For many years, the main complaint by the GOP has centered on alleged incidents of illegal fraud where it is claimed that ineligible people registered and cast ballots, for example non-US citizens and felons, or imposters who registered or voted more than once. Throughout the campaign Donald Trump repeatedly stoked up the heated rhetoric by alleging that victory would be stolen from him. After he won the Electoral College vote, he claimed (falsely) that he also won the popular vote “if you deduct millions of people who voted illegally”, with “serious fraud in Virginia, New Hampshire and California”. In fact, however, across the country, officials found next to no credible evidence for cases of voter fraud.

Suppression of voting rights

For Democrats and civil rights organizations, by contrast, the main problem has been framed as one of the suppression of voting rights designed to depress legitimate citizen participation. They routinely criticize attempts by GOP State legislatures to tighten voter ID requirements and restrict polling facilities, making it harder to vote, especially for minorities and the elderly. Here the evidence about the impact of implementing stricter registration requirements in depressing the vote is somewhat clearer although debate continues about the size of any effect and which party benefits.

Maladministration

On polling day, journalists highlighted accidental failures in the nuts-and-bolts of electoral maladministration, including human errors and machine breakdowns in registration and balloting. For example, the New York Times reported that scattered problems occurred on November 8th in several polling places, with long lines in North Carolina, Virginia, New York, and Texas, sporadic breakdowns for the electronic register in Durham NC, and malfunctioning voter verification in Colorado. These types of glitches fueled requests by Jill Stein, the Green party candidate, for recounts to verify the results in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, demands backed later by the Clinton campaign.

Yet in fact, although detecting some minor technical flaws, when they ended on December 12, the recounts in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin confirmed the declared winner. In Wisconsin, for example, after recounting over 3 million ballots, fewer that 1,800 votes switched columns. There is a good case to be made for automatic random audits of the vote count in all states, as a standard procedure to strengthen public confidence in the process, but any errors are unlikely to determine the overall winner.

Cybersecurity

It only emerged with full force after polling day that the most fundamental challenge to American elections has arisen not from any of these issues at all but from the vulnerability of open societies to disinformation campaigns and breaches of computer security. CIA and FBI officials report that senior Russian officials directed the hack into the computer server of the Democratic National Committee and the private emails of Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman, John Podesta. The intelligence services followed the breadcrumbs all the way back to the Kremlin and concluded that the intrusions were designed both to undermine confidence in US democracy and (probably) to help get Trump elected. Russian attacks were weaponized through the stream of stories reported in mainstream journalism. The stream of Wikileaks materials generated a constant series of negative news cat-nip about the goings-on within the Clinton campaign. The plethora of fake news on social media also fueled home-grown conspiracy theories and memes among the tin-foil hat brigade.

(As a point of disclosure, I take this personally. Based on the security firm Volexity, on 13 December the New York Times reported that my own Harvard Kennedy School research paper on “Why American elections are flawed” was downloaded, infected by the Dukes with malware, then circulated immediately after the election under a phony Harvard email in a phishing attempt.)

This problem is not confined to the US by any means and nor is it novel; Germany’s intelligence agency reported on 13 May 2016 that Russia was behind an attempt to hack the German Bundestag and Angela Merkel’s CDU party in 2015, with cyberattacks on government institutions going back for more than a decade. The severe disruption caused by disinformation in the US campaign has heightened concern for European countries heading to the polls next year, where campaigns in France, Italy and Germany are vulnerable to these techniques.

Evaluating the electoral performance of American states

The 2016 campaign therefore saw multiple complaints about how American elections work. These sorts of charges are likely to damage public trust in institutions, undermine confidence in the electoral process, depress turnout, and fuel protests questioning the legitimacy of Trump’s inauguration.

Given divergent claims by each party, is there independent and reliable evidence to support criticisms about the performance of American elections? And, where problems did occur, were these more common in states won by Trump or Clinton?

EIP's survey methods

To evaluate performance, the Electoral Integrity Project (EIP), an independent academic project based at Harvard and Sydney Universities, conducted an expert survey of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity. EIP has used this method for the last five years to evaluate the quality of parliamentary and presidential elections around the world, including the 2012 and 2014 US elections. This technique is commonly used for evaluating performance in the absence of directly observable indicators and it is similar to that employed for the Perception of Corruption Index by Transparency international.

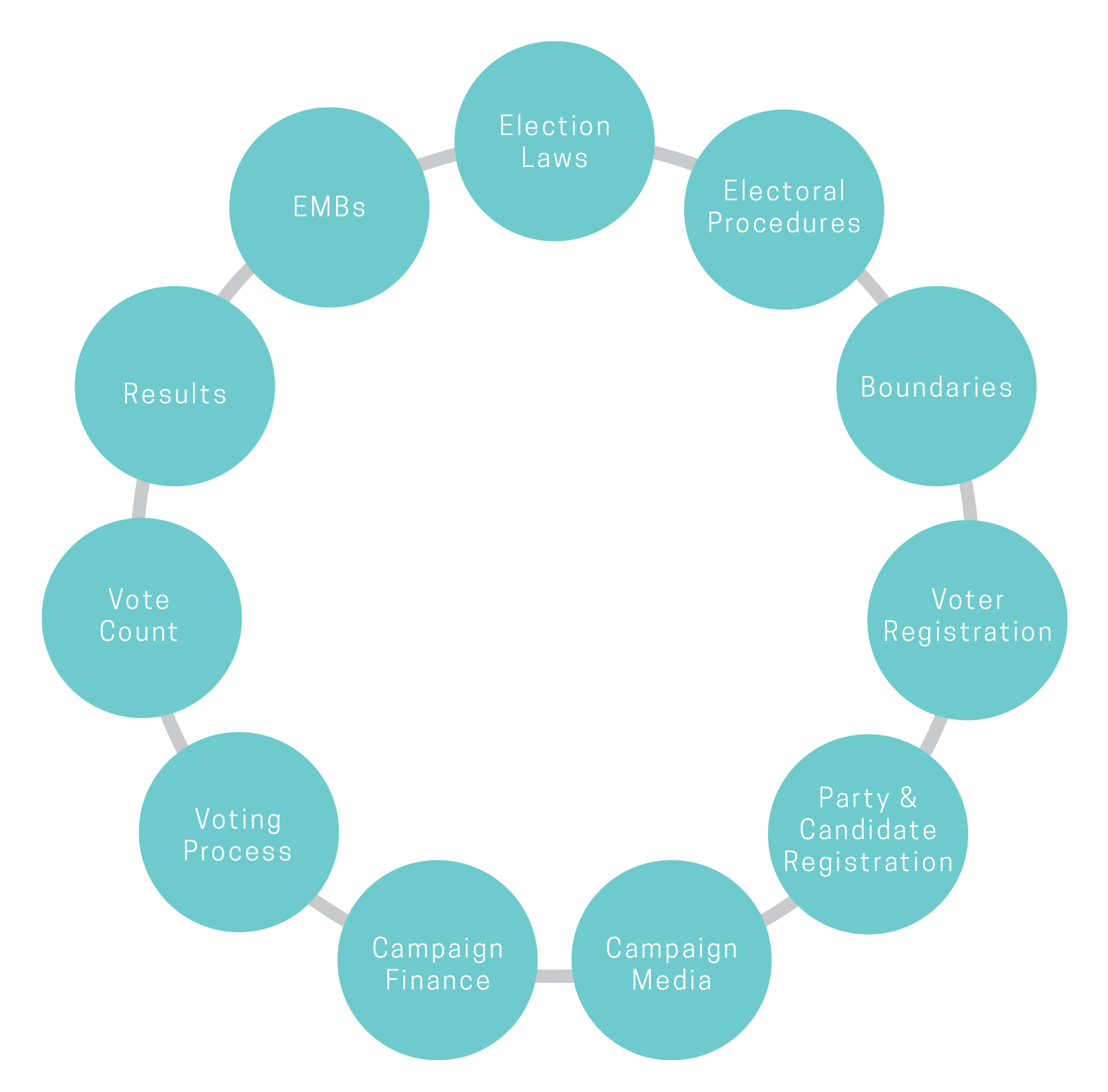

The core concept of ‘electoral integrity’ refers to international standards and global norms governing the appropriate conduct of elections during the pre-election period, the campaign, polling day and its aftermath. In this regard, it is a far broader concept than simply a focus on the final stages of irregularities in the electoral register, fraudulent votes being cast, or miscounted ballots.

Experts

Experts can be defined in many ways. The research gathered evaluations from 726 political scientists based in local universities in each state. Respondents were asked to evaluate electoral integrity in their own state two weeks after polling day. Given the diversity of issues, the survey used 49 core indicators which were then grouped into eleven categories reflecting all stages throughout the electoral cycle, during the pre-election, campaign, polling day and its aftermath. Each category rating is standardized to 100 points. The dataset also includes a summary 100-point PEI Index from summing all 49 indicators.

Several characteristics of states were also gathered, such as the partisan composition of state legislatures, the share of the vote in the 2016 presidential race, and the marginality of the contest. Details about the individual experts were also collected, such as their age, sex, and ideological positions, to see whether these characteristics were systematically associated with evaluations of electoral integrity.

Reliablilty

Is the data reliable? It can be argued that political scientists are not neutral judges, given the well-known academic bias towards supporting liberal democratic values. Indeed, the whole idea of independent ‘experts’ has come under dispute in this populist and hyper-partisan age.

But the external validity of the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity Index has been widely tested in previous research and found to be strongly correlated with other standard sources of evidence, like Freedom House and Polity.

The survey also asked election experts to judge the performance of U.S. elections on a wide range of issues in their own state, such as whether elections were well managed, votes were counted fairly, and newspapers provided balanced election news, without any reference to political parties or the party in control of the state house.

It is important to be cautious when interpreting absolute rankings since differences between states were often relatively modest and the number of responses was limited in some states, such as Utah and North Dakota, although none of these are in the worst performing cases.

Finally, the survey measures expert Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, taken as both a proxy for the underlying phenomena and as important construction of social reality in its own right. If people believe that elections are flawed, this is a problem, irrespective of their actual performance. The PEI index has been widely cited by scholars and practitioners around the world, becoming the most comprehensive measure for comparing electoral performance from Australia to Zimbabwe.

The results supplement other sources of evidence which will become available to test the external validity of the EIP estimates in due course, including comparison of state performance indices (such as voting wait times and turnout rates), the forensic analysis of precinct-level voting statistics, scrutiny of credible complaints and legal cases, surveys of poll-workers and local electoral officials, analysis of social media, and surveys of public opinion.

Ranking electoral integrity and malpractices across US states

Source: PEI-US-2016

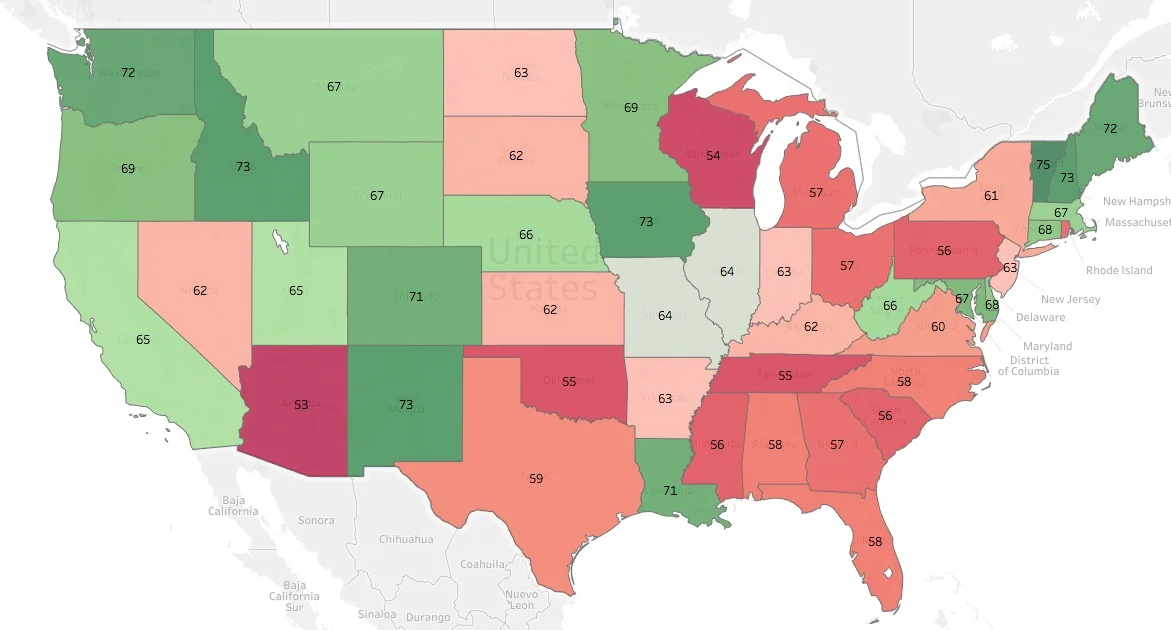

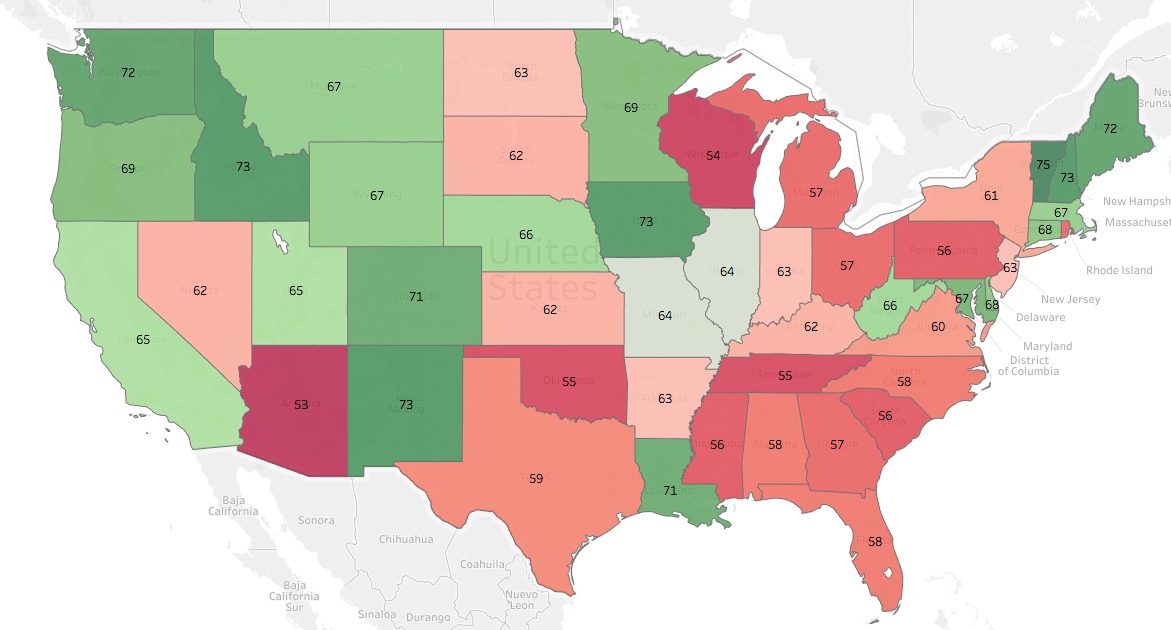

Figure 1 maps how experts evaluated the 2016 elections across all 50 US states and DC.

Regional performance

The patterns show that the south remains the region of America which experts assess as having the weakest electoral performance. The Supreme Court ruled that voting restrictions in the South were a bygone problem, eliminating Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act which had required states with a history of racial discrimination to get Department of Justice approval before changing voting laws. Evidence from these expert evaluations, and from recent GOP State House shenanigans in North Carolina to restrict the power of the Governor before Democrat Roy Cooper takes over, suggests that this may have been unduly optimistic. Rust belt ‘Blue Wall’ states were also seen as problematic. By contrast experts assessed the quality of elections more positively in the Pacific West and New England.

State performance

But state performances varied even within major regions. Overall, states scoring as worst in the perceptions of electoral integrity index in this election were Arizona (ranked last), followed by Wisconsin, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Mississippi. Several of these states had also been poorly rated previously in the 2014 Pew Election Performance Index. By contrast, the U.S. states which experts rated most highly in electoral integrity were Vermont, Idaho, New Hampshire, and Iowa.

Figure 2: State performance across 11 stages in the electoral cycle, 2016

Note: Each scale is standardized to 100-points.

Source: PEI-US 2016

What are the main problems?

The exact reasons underlying varying performance still needs probing further. Problems can arise at any stage of the electoral process – not just at the ballot box. To dive deeper into the data, Figure 2 looks at how experts evaluated state performance across each of the eleven stages of the 2016 contest.

The results show that the stages of the vote count, the voting process, and the role of electoral authorities have a fairly clean bill of health across nearly all US states. By contrast, however, according to experts, far greater weakness in many American states concern the stages of district boundary delimitation, state electoral laws, campaign media, and political money.

Clearly some of these issues are already on the mainstream reform agenda. Allegations of voter fraud received massive attention and the reform of state electoral laws was also widely discussed in the campaign, following the passage of several restrictive voting and registration procedures which were subsequently struck down by the courts, such as in North Carolina. The need to reform the role of money in politics was covered during the campaign, including playing a big part of Bernie Sanders’ campaign. Donald Trump’s populist rhetoric also railed against corruption in politics, including the nefarious role of beltway lobbyists and self-interested members of Congress. In terms of campaign communications, the impact of fake news and Russian meddling in the campaign have both emerged as major issues of bipartisan concern after November 8th, despite some poo-pooing by Trump.

By contrast there are other broader issues about campaign media which should raise serious concern, as reports by Harvard’s Shorenstein Center have highlighted, including the lack of substantive policy discussion during the campaign, the false equivalency standards of journalism, and the overwhelmingly negative tone of news coverage.

Moreover the issue of gerrymandered district boundaries, regarded by experts as the worst aspect of U.S. voting procedures, was never seriously debated throughout the campaign. The practice ensures that representatives are returned time and again based on mobilizing the party faithful, without having to appeal more broadly to constituents across the aisle, thus exacerbating the bitter partisanship which plagues American politics. Gerrymandering through GOP control of state legislatures has also led to a systematic pro-Republican advantage in House districts which is likely to persist at least until 2022. In 2016 House Republicans won 241 seats out of 435 (55%), although they won only 49.1% of the popular vote, a six-percentage point winners bonus.

Where malpractices occurred, were they in states won by Trump or Clinton?

So how far does the performance of states relate to party control of state legislatures? Figure 3 shows expert assessments of each of the stages during the electoral cycle compared with which party controlled the State House.

The results clearly demonstrate that, according to the expert evaluations, Democratic-controlled states usually had significantly greater electoral integrity than Republican-controlled states, across all stages except one (the declaration of the results, probably reflecting protests in several major cities following the unexpected Trump victory). The partisan gap was substantial and statistically significant on the issues of gerrymandered district boundaries, voter registration, electoral laws, and the performance of electoral officials.

Figure 3: Performance across 11 stages in the electoral cycle by state control

Given this pattern, not surprisingly there was a clear tendency for Trump to win more states with electoral malpractices (see Figure 4), while Clinton won more states with electoral integrity. We do not claim, as we do not have sufficient evidence, that Trump won these states because of malpractices. But the correlation is clear. Thus, throughout the campaign, and even afterwards, it was Donald Trump who repeatedly claimed that the election was rigged and fraudulent. In terms of votes being intentionally cast illegally, the strict meaning of ‘voter fraud’, there is little or no evidence supporting these claims. But if the idea of integrity is understood more broadly, there is indeed evidence from this study that US elections suffer from several systematic and persistent problems - and Donald Trump and the Republican party appear to have done well in states with the most problems.

Figure 4: Electoral integrity by Trump's share of the vote

Source: PEI-US 2016

The urgent need for reforms addressing major problems

Elsewhere our research has demonstrated that the 2012 and 2014 American elections ranked poorly in comparison with many other countries, with the United States scoring the worst in electoral integrity among similar Western democracies. The US also ranks 52nd out of all 153 countries worldwide in the cross-national electoral integrity survey. The comparison is even worse for the issue of district boundaries, where the U.S. score is the second lowest in the world.

This comparison of US states dives further into the reasons behind this dismal performance. We have repeatedly warned about the consequences of these problems, with my book on Why Electoral Integrity Matters demonstrating the consequences for eroding public faith in political institutions and confidence in democracy – and suggested several practical remedies.

Whether any of these urgent reforms can be implemented in the current climate of bitter partisanship, and at a time of authoritarian push-back against basic democratic principles and practices at home and abroad, remains to be seen. But America need a bipartisan commission to tackle the real short-comings in U.S. elections, and states need to implement reforms even if the federal government is paralyzed, including by strengthening electoral security and voting rights, limiting partisan gerrymandering, improving fair and accurate campaign communications, and cleaning up campaign finance, and not be endlessly distracted by the spurious charges of voter fraud which continually featured as shiny baubles in the campaign. America can and will continue to debate all sorts of public policies. But countries which fail to reach a consensus about the legitimacy of the basic electoral rules of the game, especially those with deeply polarized parties and leaders with authoritarian tendencies, are unlikely to persist as stable democratic states.

Bio note: Pippa Norris is the McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics, Laureate Professor of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Director of the EIP Project. Holly Ann Garnett is a PhD candidate at McGill University. Max Grömping is a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney. More details and data are available at www.electoralintegrityproject.com .

Electronic datasets for PEI-US 2016 can be downloaded here: