By Zaad Mahmood and Rahul Ganguli

Presidency University, Kolkata, India

Professor Zaad Mahmood was a Visiting Fellow with the EIP project in 2016. He helped to develop the PEI-India-2016 state survey along with Lawrence Saed (SOAS) and Ferran Martinez i Coma (Griffith). Contact: zaad.polsc@presiuniv.ac.in

India is the largest democracy in the world. The honor is largely due to the regular, participatory and successful conduct of elections in the country. The 2014 parliamentary elections had an electorate of more than 800 million (larger than the combined electorates of North America, Europe and Australia), and involved more than a 18 million poll workers (Press Information Bureau 2014). As Palshikar (2012) points out elections have become an indispensable part of the governmental system and have become ingrained in the political common sense of India. Elections are considered central to the management of ethnic and regional conflicts, the balance achieved between the central government and state and local authorities and the pride Indians take in their democratic institutions. (Foreign Affairs 2008).

Despite the overall success of the massive electoral exercise, several problems have been reported, including electoral violence, lapses in voter registration, unequal access to finance and media. Media reports during the 2014 elections were replete with news of vote buying (Mahmood 2015). Notwithstanding the shortcomings, the Indian parliamentary election ranked above average in the worldwide 2016 Perceptions of Electoral Integrity index produced by the Electoral Integrity Project, due to its favourable ratings in election management, laws, electoral procedures, counting and result announcement. On most criteria, the position of India was higher than South Asian mean, as well as global mean scores.

Although the performance of EMB in India is commendable, sub-national differences in performance and efficiency has remained relatively unexplored. In India, sub-national elections have great importance as the federal framework endows provinces with significant political- administrative powers (Yadav 1999). Anecdotal evidence from state elections suggest that many maladies afflicting parliamentary elections can be noted in the sub-national elections also. Take note of the following news headlines and magazine articles that preceded assembly election in five sub-national states of India during 2015-2016:

Polling in Tamil Nadu’s Aravakurichi postponed over bribery concerns

The 'promising' world of Tamil Nadu politics: From freebies to bans

Corruption the biggest issue in Bengal polls

Bihar Elections 2015: NDA Campaign Torn Between PM Modi's Economic Reforms and BJP's Hindu Agenda

Kerala polls: Caste and community leaders could hold the key this time

Election Commission stipulates special arrangements for electoral fraud in Kannur.

Perceptions of electoral integrity

Is there more systematic and reliable evidence about how Indian states experienced these types of problems during recent elections, supporting the news media claims? To examine this issue, the Electoral Integrity Project used an expert survey to evaluate the 2015-2016 state assembly elections in Bihar, Assam, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The study was directed by Professor Zaad Mahmood (Presidency University) and Lawrence Saez (SOAS, London) and implemented by Dr Ferran Martinez I Coma (Griffith University). Sagnik Dutta of Cambridge University provided research assistance.

The Perception of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index, devised by scholars in Harvard University and University of Sydney, is a well-recognised measure of quality of elections across the world. The PEI index measures the quality of elections to evaluate, identify and analyse the lacunae in the electoral process. The Perception of electoral integrity index, helps us to study the “quality “ of elections that may be flawed due to unfair regulations, disqualification of opponents, manipulation of media, unfair disparities in political campaign finance, violence and so on (Norris 2015). The PEI consists of 11 parameters which include election laws, constituency boundaries, party and candidate registration, campaign finance, vote count, election procedure, campaign media, voter registration, voting process, result transmission, and election management bodies. It deconstructs these into the Pre-election, Campaign and Election Day and Post-election phases.

The state assembly elections in Bihar held in Oct-Nov 2015 and Assam, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Kerala held during April- May 2016 were evaluated by experts (academics affiliated to educational institutions with publications on state elections/politics). Forty experts were contacted for each state a month after polling to evaluate the quality of elections.

Sub-National Electoral Integrity

The five states are geographically diverse with Assam in the North East, West Bengal and Bihar in the east, Tamil Nadu and Kerala in the south of India. The nature of political contest is very diverse across the states with two regional parties competing in Tamil Nadu, primary contest between regional and national parties/alliances in Bihar, West Bengal, contest between two national parties in Assam and between two stable alliances in Kerala. The sub national states also have considerable difference in socioeconomic indexes. The state are marked by divergence in rates of literacy, economic growth, urbanisation, all factors that have consequences for quality of elections.

How do selected Indian states compare in electoral integrity?

PEI shows that significant variations in the quality of elections across the states. Bihar, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu have PEI score above the Indian national average, indicating relatively free and fair elections. In contrast, West Bengal and Assam fall below the India score, indicating below par elections.

Fig 1. Sub national electoral integrity of India

Source: PEI-India-2016

The quality of elections across the sub-national states raise questions about the conventionally accepted relation between development and democracy. Traditional modernisation theory suggests a causal relation between democracy and economic development. The basic assumption is that there is one general process of which democratisation is the final stage (Przeworski and Limongi 1997). Democratic government is correlated to economic development. In this regard the quality of elections in Tamil Nadu (high economic development) or Kerala (high human development) somewhat corroborate expectations. However the quality of election in Bihar (one of the poorest states of India) and West Bengal (medium per capita state) appear counter intuitive.

Fig 2. Electoral Integrity and Development

Source: PEI-India-2016

A simple measure of Per capita Net State Domestic Product and PEI score illustrates the non-correspondence between quality of election and development. As the graph reveals all the states have a higher per capita income than Bihar, which also happens to have the maximum proportion of its population living below the poverty line. Bihar also has the lowest literacy rate with only 62 percent of its population literate as compared to 94 percent in Kerala. It shows that while socio-economic development and its importance cannot be neglected, a more holistic approach, is required to identify the reasons could and do influence the quality of elections (Norris et al. 2016).

Evidence

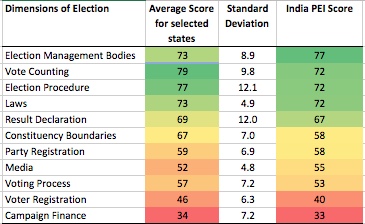

Disaggregated analysis of the 11 stages of election process reveal some very important strengths and weaknesses of Indian elections and highlights the sub-national variations.

Figure 3. PEI scores for 11 dimensions of electoral cycle

Source: PEI-India-2016

Fig 3 presents the PEI scores for each state across the 11 specific dimensions of election. The figures in red represent poor performance while green represent good performance while amber represents an intermediate performance. Analysis of the PEI results highlight the following:

First, election finance is the Achilles heel for democratic elections in India. The use of money for vote buying and unequal access to funds for parties seriously undermine the legitimacy and quality of elections in India. Tamil Nadu performs the worst with 24.6 corroborating the newspaper headlines about big money in elections.

Second, voter registration and media are issues of concern for the election system in India. In terms of access to media Assam has the lowest scores while again Kerala seems to be the best among the states. Incidentally the 2014 elections in India also highlighted finance and media as important weakness undermining electoral integrity (Mahmood 2015).

Third, voter registration and party registration reflect significant variation across the states. On both these counts the sub-national states perform better than Indian average possibly by virtue of being closer to the ground with smaller elections compared to the national elections. In this regard West Bengal is clearly a laggard with the worst performance. Party registration captures the dimension of political and partisan freedom and fairness. West Bengal performs worst in this dimension which is quite understandable in the context of wide scale reports of intimidation and violence (Indian Express 2016).

Fourth, related to party registration the voter registration is the process of voting. In this context Bihar has the best record with a score of 63.72. The results are surprising as Bihar has had a long history of electoral violence and intimidation which seems to have improved significantly. In comparison Assam and West Bengal are again among the worst performing states in this regard. Interestingly Kerala which is a high performing state in other respect is poor performer in this regard. Electoral violence, in states like West Bengal and Kerala reflect entrenched partisan politics, as compared to Bihar where violence is more on the lines of caste, and other social parameters. The comparatively lower score of Assam in ensuring free and fair polling is expected given the interethnic violence, fueled by issues of indigeneity and ‘illegal’ migration (Saikia 2015).

Fifth, quality and impartiality of election laws are very high across the states. The institutional dimension of elections such as election procedures, result declaration, vote count, and election management body have high scores. The sub national performance on these dimensions although satisfactory show maximum divergence across states. What is interesting is that all of the dimensions concern the performance and assessment of election management bodies.

Fig 4. Variations in the dimensions of Electoral Integrity

Source: PEI-India-2016

Fig 4 reveals that the most variation in electoral integrity across the states is due to procedural and institutional factors. Evidently in all of these factors Bihar scores the highest across all dimensions while West Bengal performs worst in most. The election commission of India performs these functions with their representatives in the sub-national states and the state administration. The variation in these dimensions suggest that despite institutional similarities, the operation of the EMBs is conditioned by region specific factors, such as administrative ethos, quality of governance and bureaucratic efficiency. The ability to hold free and fair elections with proper procedures requires not only institutionally independent EMB but also affected by the overall governance in the state

The ability to hold free and fair elections with proper procedures requires not only institutionally independent EMB but also affected by the overall governance in the state. Such an argument is reinforced by perceptible differences in the performance of Election Commission. For example the Election Commission played an active role in Bihar to downplay possibilities of communal tensions by clamping down in hate speech (Nayak 2015). In contrast campaigns based on hate speech with communal dimensions such as that in Assam against Bengali Muslims were not dealt in a similar manner. There have also been accusations against the EC in West Bengal, that they have tended to normalise incidences of violence during the electoral process, simply on the grounds that it has occurred away from the polling booths. It has been reported that despite repeated assurances by the EC, central forces were not used for area domination before the polling day (Economic Times 2016). Such incidences can be understood to be a part of a broader scheme of failure in governance which have contributed to poorer performance in the PEI index despite advantages in the socioeconomic fronts of the said states.

Despite the enormous success of electoral processes in India, issues of money in election, biased media, limitations in voter registration and violence subvert the democratic ethos. The success of elections in India depends on the ability to limit the factors that undermine equitable party competition, transparency, accountability, inclusive participation, and public confidence in the integrity of the political process. Along with institutional innovations to make elections free and fair, it must be remembered that electoral system operates within a wider context of government. As the sub-national studies reveal, overall governance has correspondence with electoral propriety and institutional effectiveness. Efforts to make election free and fair have to address the wider issues of governance.