BY: Erik Asplund, Lars Heuver, Fakiha Ahmed, Bor Stevense, Sulemana Umar, Toby James and Alistair Clark

Originally Published 02/05/2021 in the International IDEA Blog

Image credit: Republic of Korea National Election Commission

At the start of the pandemic, many countries postponed elections. From June 2020, the trend shifted to holding elections. Thanks to information sharing and peer-to-peer exchanges, election authorities gained an understanding of the risks and prevention/mitigation measures. To date, more than 100 countries and territories have held national or subnational elections that were either on schedule or initially postponed with health and safety measures. But what measures have been introduced so far? What measures have been adopted by countries that have held elections? Are the measures respected by stakeholders? Was voting safe?

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

This article helps to address these questions by presenting information on the health and safety measures introduced into polling stations around the world in 2020. Data was collected from electoral management bodies (EMBs), state institutions, media, and election observation reports from 52 national elections (in 51 countries) in 2020 on how in-person voting was implemented. This was the vast majority of the countries that held national elections but which also had cases of COVID-19 at the time. This analysis forms part of a series that has covered campaign limitations and will cover other parts of the electoral cycle, including special voting arrangements and international elections observation. It forms part of an ongoing study between International IDEA and the Electoral Integrity Project on COVID-19 and elections.

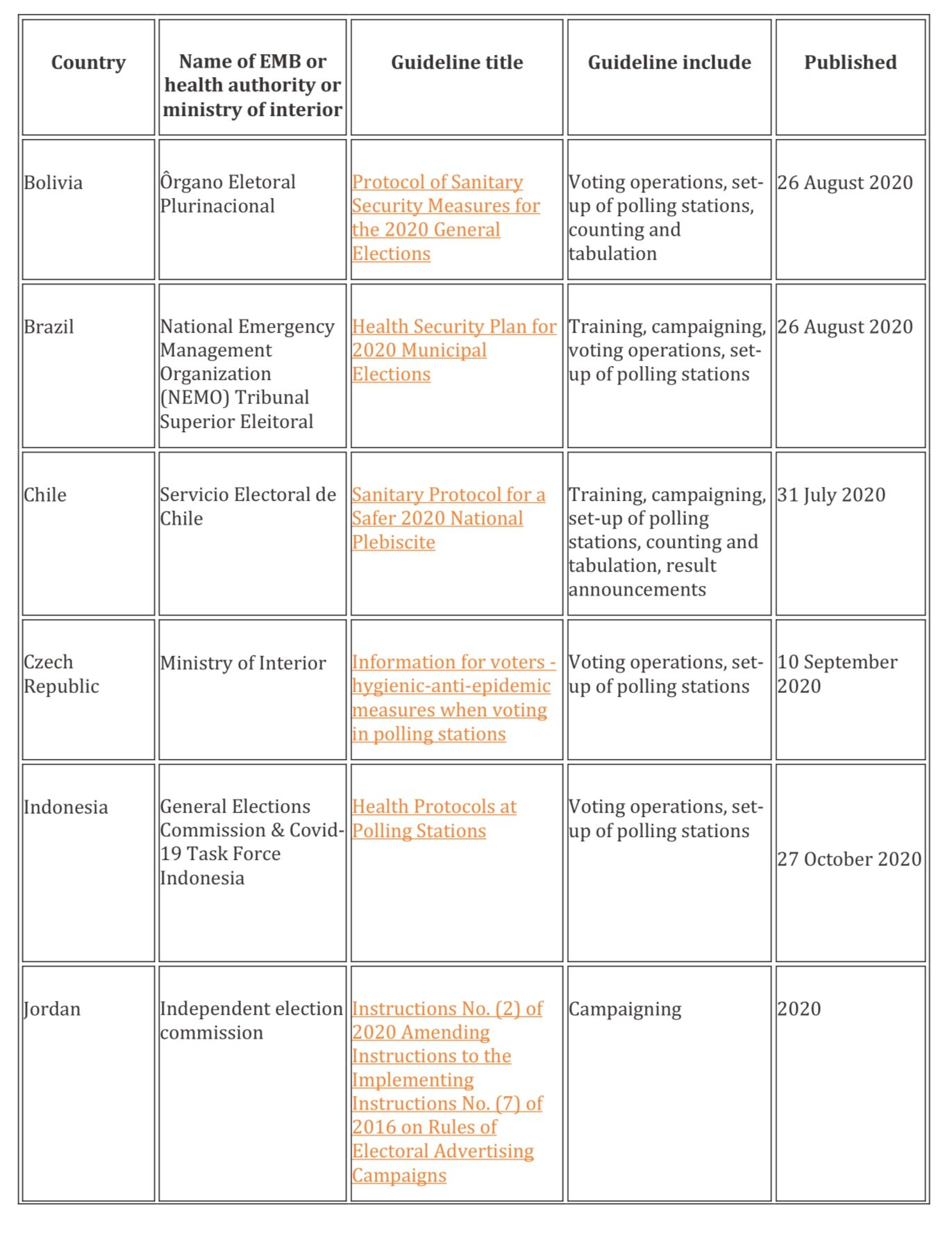

Health and safety guidelines

One of the first steps that EMBs or state institutions took to limit infection risk, often in collaboration with health ministries, was to introduce health and safety guidelines for the election (See Table 1). The guidelines typically focused on the voting operations or the entire electoral cycle (nomination processes, training, voter registration, campaigning, voting operations, set-up of polling stations, counting and tabulation, result announcements). Out of this sample of 20 sets of national guidelines from 19 different countries, 1 covered nomination processes, 6 training, 3 voter registration, 7 campaigning, 18 voting operations, 18 set-up of polling stations, 11 counting and tabulation, and 1 addressed result announcements.

Table 1. COVID-19 health and safety guidelines by country

Source: Authors, constructed using EMB and country information.

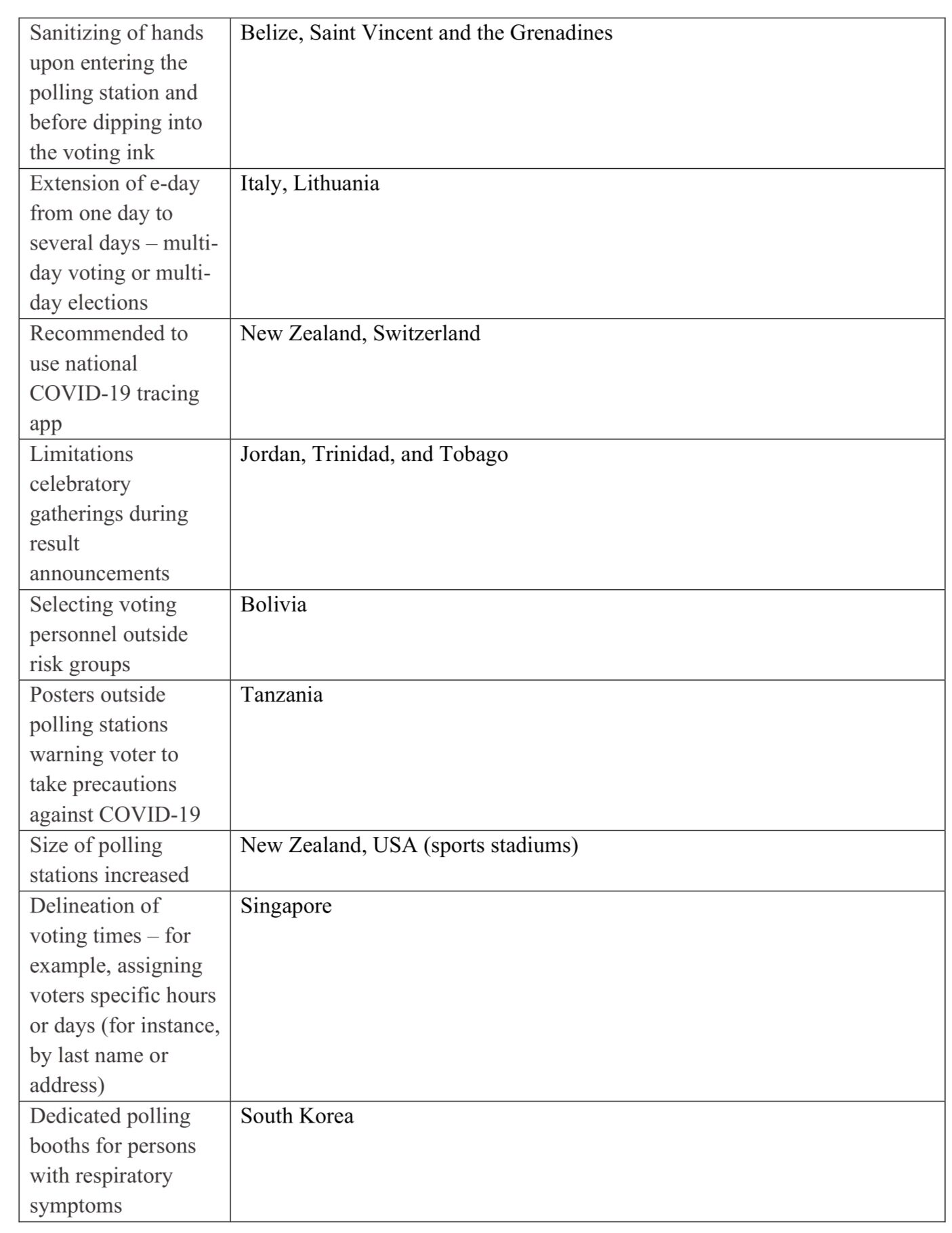

Health and safety measures in polling stations

Health and safety measures for polling stations typically included rules on social distancing, the use of handwashing facilities (or hand sanitizers and disinfectants), ventilation of the polling station, the cleaning of voting materials, and personal protective equipment for polling officials. Almost all countries that have held national elections in 2020 have adopted combinations of these measures (see Table 2).

Beyond these general measures, many countries introduced innovative and extraordinary measures to decrease infection risk. These measures are country and election specific, which may have been exacerbated by spikes in coronavirus. In Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Trinidad and Tobago, the EMBs organized mock polling stations to simulate election day and see whether the new practices would work. In Ghana and Malawi, "COVID-19 ambassadors" were tasked to manage compliance with voters' safety measures. In Jordan and Venezuela, the military took on this role. In Belize, Bolivia, Chile, Italy, Poland, and Singapore, priority queues were in place. Elderly, pregnant women and other vulnerable people could skip the lines at polling stations. For the Bolivian Presidential election, the voter rolls were divided into two-time slots for voting between 08:00-12:30 and 12:30-17:00 to prevent clustering. Commercial activities were also restricted within 100 meters of polling stations, and voting personnel were selected outside the risk groups (between the ages of 18 to 50). In Romania, upon arrival, the elector's temperature was measured at the polling station entrance, and the maximum number of persons at the same time at a polling station was set at a maximum of 15. At the entry and exit, voters had to disinfect their hands. Pens were provided at the polling stations. In Switzerland, besides adhering to the standard COVID-19 mitigating protocols, people were also encouraged to use the Swiss COVID-19 App. The App's purpose is to help stop COVID-19 from further spreading and to detect early possible second wave and tackle it effectively through contact tracing. As of 23 September, it has been downloaded over 2 million times.

Were measures respected?

Based on a review of 31 Electoral Observer Mission’s (EOMs) reports from various missions in 2020, 13 reports on Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Montenegro, Myanmar, Niger, Serbia, Seychelles, and Tanzania suggest that restrictions were often not consistently respected and poorly enforced. In general, EOMs stated that compliance to health and safety measured in place varied inside polling stations, and enforcing restrictions outside polling stations was difficult most of the time. The use of masks and disinfectant was followed in most cases. Adherence to social distancing rules turned out to be to most challenging in many cases due to polling stations not being spacious enough for regulations to be adhered to.

Table 2. Health and safety measures introduced during the 2020 national elections to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

Source: Authors, constructed using International IDEA, media reports, and EMB data. Note: This table is based on 51 countries that held 52 direct national elections and referendums from 21 February until 31 December 2020. All of the countries included in the table had one or more confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection. The table does not cover health and safety measures introduced during national by-elections or subnational elections.

Was in-person voting safe?

Have all these reforms helped to protect public health? To date there have been very few reports linking voting arrangements with community transmission. However, some studies have been carried out and are at times contradictory. For example, in one study, focusing on the Wisconsin, USA, primary election showed “statistically and economically significant association between in-person voting density and the spread of COVID-19 two to three weeks after the election” whereas another study focusing on the City of Milwaukee from the Wisconsin CDC found no clear increase in cases, hospitalizations, or deaths. Beyond the US, health authorities in South Korea concluded that no local transmission occurred from the Parliamentary election held in April 2020, and a scientific article published in August substantiated this claim. In contrast, a French study on municipal elections in March 2020 suggested an increase in numbers of hospitalizations due to the polls, but mainly in areas already showing high transmission levels. However, they found that the election did not contribute to virus transmission in areas with already low levels of COVID-19.

There needs to be caution in interpreting this evidence. Without a consistent and robust estimation methodology which can link voting arrangements directly as a cause of transmission to individual voters, separate to ordinary community transmission, it is difficult to know when and where the virus was in fact caught. Variations in data availability between countries, and different methods and approaches among studies, make it very difficult to come to general conclusions. Media reports could also be less reliable in this respect; focusing on the anecdotal rather than aggregate picture-and may have the potential to spread misinformation. Nonetheless, Votebeat, a nonpartisan reporting project, provides some anecdotal evidence that many US poll workers tested positive during the November 2020 Presidential election.

Conclusion

Although risks remain, it appears that countries are more willing to hold elections because of an improved understanding of the virus. Time has also elapsed since the pandemic started, which has enabled lesson drawing from overseas, risk management plans to be adapted, and election planning to take place. Health and safety measures will clearly require further investment in elections to protect the safety of staff, campaigners, and votes. They will also be needed to assure citizens that voting is safe—so that turnout is not affected. The early publication of guidelines will help them to be implemented—and mechanisms for enforcement need to be considered by policy makers too.

Main findings on health and safety measures in polling stations

Health and safety measures have been adopted by almost all countries running elections and were similar across countries.

Some countries have adopted more safety measures than others.

Compliance to health and safety measures varied inside polling stations, outside was difficult to enforce. Problems related mostly to space so that social distancing could be adhered to (rarely respected or possible)

The use of masks and disinfectants seems to be in place and broadly respected inside polling stations in most countries.

Further investment will be required in health and safety mechanisms for elections to ensure health and safety, but also to prevent voter turnout declines.

About the Author

Erik Asplund is a Programme Officer in the Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA. He is currently managing the Global Overview of COVID-19: Impact on Elections project. Other focus areas include Electoral Risk Management, Financing of Elections and Training in Electoral Administration with an emphasis on BRIDGE and Electoral Training Facilities.

Lars Heuver is a graduate student in Peace and Conflict Studies at Uppsala University, currently doing an internship at International IDEA. Fakiha Ahmed is a Master's student in Peace and Conflict Studies at Uppsala University and is currently doing her internship at International IDEA. Bor Stevense is a second-year Masters student at the University of Uppsala for the Peace and Conflict Studies programme, currently doing an internship at International IDEA. Sulemana Umar is a second-year Masters's student at Lund University pursuing International Development and Management Programme. He is currently an intern at International IDEA. Toby S. James is Professor of Politics and Public Policy in the School of Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication Studies at the University of East Anglia. His most recent books are Comparative Electoral Management (Routledge, 2020) and Building Inclusive Elections (Routledge, 2020). He is co-convenor of the Electoral Management Network. Alistair Clark is Reader in Politics at Newcastle University. He has written widely on electoral integrity and administration, electoral and party politics. He is the author of Political Parties in the UK, 2e (Palgrave 2018). He tweets at @ClarkAlistairJ.

Lars Heuver, Fakiha Ahmed, Bor Stevense, Sulemana Umar, Toby James and Alistair Clark